Mapping resiliency, sort of

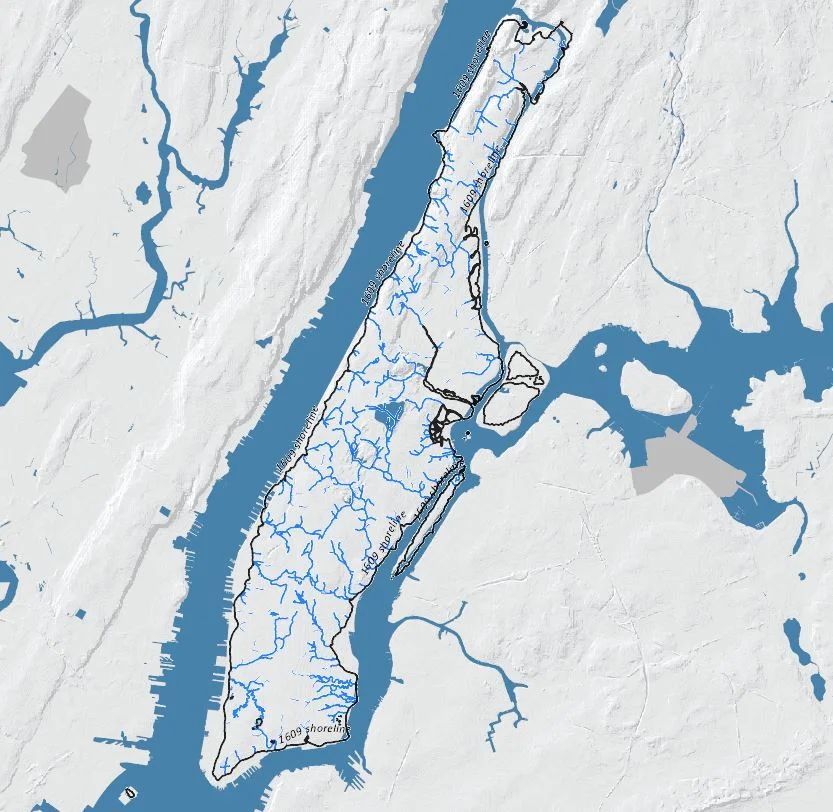

Looking at the 2013 New York City Hurricane Evacuation Zones Map, it's not difficult to see a relationship to the original coastline of Manhattan. The image "Growth of Manhattan Island 1650-1980" from the fantastic book, The Lower Manhattan Plan: The 1966 Vision for Downtown New York (Carol Willis, editor. Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2002.) shows very clearly the expansion of the Lower Manhattan shoreline over a time period of 330 years. The oasisnyc.net map overlays the 1609 shoreline, ponds and streams on today's Manhattan. The Sanitary Map from 1865 shows the expanding urbanization of Manhattan and a 7 year old Central Park via the in-progress "Commissioner's Plan of 1811", ie the Grid. You see many intact ponds and streams as well as Manhattan's namesake hilly topography. The Lenni Lenape name for the island, Mannahatta, likely meant land of many hills.

So, resiliency in the face of climate change's rising sea levels and super storms. My concern, in addition to actually designing, tweaking and improving infrastructure, is how can we educate New Yorkers about the climate realities of their city, and get them participating in a dialog? The successful re-imagining of important infrastructure and junctions in all five boroughs will take the input of the people, and the willingness of designers, city government and policy makers to learn how to engage communities effectively.

I believe in the power and impact of visual, spatial, and biological interventions to engage people in public spaces and areas. These could be little nuggets of color, signage,trees, and other way-finding that have the effect of causing a moment of pause, reflection and ideally, understanding. Part of the challenge is changing the way we often walk through our day-to-day lives as city dwellers. The ability to make astute observations is dependent on that pause + reflection = understanding equation. However, the impact can also be felt with a subconscious understanding that one is experiencing good design. When you enjoy moving through a space, lingering here, and not there, that is good design and people feel that, even if they don't consciously realize it.

Moving forward, how do we design to the p + r = u? We don't want to be pedantic, or too literal, we want to entice, sparkle, create curiosity, wonder and thrill, while still talking about issues related to resiliency and infrastructural longevity. This is a conversation many architects and urban planners/designers are having currently.

Bureaucracy can be a roadblock for exciting ideas, but it can also present the kinds of limitations designers are well versed in dealing with. It makes sense that elected officials, community, etc should be a part of the conversation, otherwise they are also in danger of not understanding the power and logic of good design and may find themselves comforted by the most basic and unimaginative solutions to serious problems. Any design solution perceived as a risk has the potential to become a liability; but the reality is that all endeavors that seek to solve or lessen big problems are risky. I have seen firsthand how government entities deliberately choose bad design, because they don't want to be accused of wasting money. Or conversely choosing an expensive “starchitect” design, in order to justify their desire to develop a space or place. Great design need not be more expensive than bad design. In fact, it can potentially cost less. With knowledgeable and passionate designers, a collaboration with a client can yield results that have benefit far beyond the original intended project parameters.